The Beginnings

Originally known as the King Charles Spaniel, the Cavalier is thought to have come to Europe from Japan sometime during the early 16th century, probably as a royal gift. It’s believed to share a common ancestry with the Pekingese and the Japanese Chin, and early portraits of Cavaliers show a marked resemblance between these 3 breeds. The dogs were rare and expensive, and consequently for many centuries were the exclusive prerogative of royalty and aristocracy.

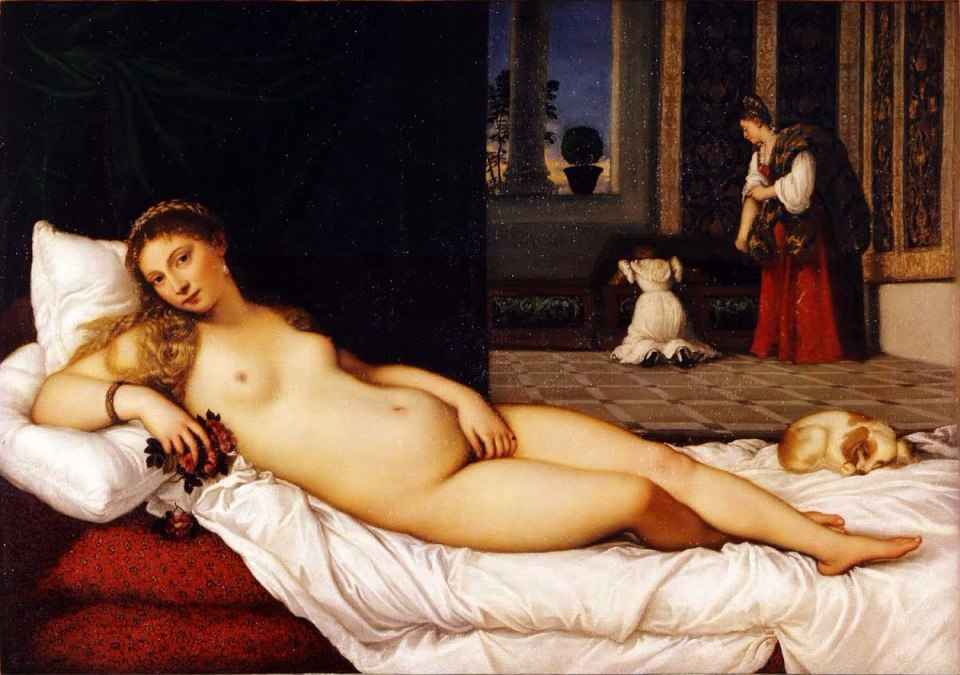

Titian’s famous Venus of Urbino (1538) shows a red and white toy spaniel as a symbol of the goddess’ seductiveness and allure

They were described as “small ladyes puppees”. King Henry VIII decreed that no dogs might be kept at Court except for “some small spanyells for the ladyes”. This is the first record of the spaniels in England.

The 16th Century – the Tudor Court

The first dog known to have been a cherished Tudor pet was a red and white spaniel called Rig, who belonged to Henry’s last wife, Catherine Parr.

Rig with his sumptuous collar

Rig had a crimson velvet collar, studded with gold, and Catherine was so devoted to him that she was buried with one of his teeth. He is clearly one of those “small laydes puppees” King Henry approved.

Mary I, eldest daughter of Henry VIII, and her husband Philip II of Spain.

By his marriage to Mary, Philip was also King of England

In this 1554 portrait of Queen Mary Tudor and her husband Philip of Spain, the two small dogs in the foreground appear to be early King Charles spaniels of this type.

Spaniels were also popular at the court of her sister Queen Elizabeth I, where a physician attributed healing powers to them! One devotee was Catherine Carey, cousin (and possibly half-sister) of the Queen. Catherine was the daughter of Elizabeth’s aunt Mary Boleyn, who had been Henry VIII’s mistress, and was one of the Queen’s few close friends.

Catherine Carey, Lady Knollys, and her daughter Lettice. Lettice was not red-headed Catherine’s only daughter to have the same colouring, lending weight to the rumours that she was Henry VIII’s illegitimate daughter

But her beautiful daughter Lettice incurred Elizabeth’s lasting hatred in 1578 when she secretly married the Queen’s great love, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. Lettice was banished from court, never to return, even when her son Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, held sway as Elizabeth’s last favourite.

The 17th Century – King Charles II and the Stuarts

In 1587 Mary Queen of Scots was accompanied to her execution by a small black and white spaniel, which was found cowering beneath her skirts after her death. It was said that the dog refused to leave his dead mistress’s body, and died of grief a few days later.

But the monarch with whom they became indelibly associated was Mary’s great-grandson, King Charles II. Charles was familiar with and loved the toy spaniels all his life.

In fact, he seems to have had his first spaniel in babyhood, as this portrait of him shows.

The Children of Charles I, by Sir Anthony Van Dyck, 1637

In this famous Van Dyck portrait of him, aged 7 with his brothers and sisters, your attention is first drawn to the huge mastiff on which the Prince is resting his arm. But in the bottom right of the picture is a brown and white toy spaniel, clearly the royal children’s much-loved pet.

The Three Eldest Children of Charles I, by Sir Anthony Van Dyck, 1635

This is another Van Dyck portrait of Prince Charles with his siblings Mary and James – and, of course, two of their spaniels! It was painted 2 years earlier than the more famous one above, and at the King’s request Prince Charles had been “breeched” beforehand, so that he could be painted in the traditional boy’s clothes of the day.

The happy childhood immortalised by Van Dyck was to become a troubled adolescence, with the King’s increasing quarrels with Parliament and the coming of the Civil War. Charles spent the first 3 years of the war with the King at the Court in Oxford, and during this time they spent together he became devoted to his father. But in March 1645 Charles rode away from Oxford in the pouring rain to take command of the King’s armies in the west; and he would never see his father again.

Charles I in Three Positions by Sir Anthony Van Dyck, 1635-6. His travails ended with his execution in January 1649

King Charles I seems to have loved his spaniels as much as his son; even having one called Rogue during his imprisonment in Carisbrooke Castle in 1648. And when Charles set sail from Holland on his journey back to England as King in 1660, the diarist Samuel Pepys noted that he was accompanied by his much-loved toy spaniels.

The King’s dogs, Pepys was enchanted to notice, ran about the ship making messes everywhere, just like those belonging to ordinary mortals. One of the dogs even shared Pepys’ barge when they were rowed ashore at Dover. He had his own footman.

For Charles, the years in between had been buccaneering and eventful.

In 1650 he landed in Scotland where he was crowned King of Scots at Scone on New Year’s Day of 1651. But for Charles the expedition had always been about England; and later in 1651 he made a bold attempt to invade England with a Scottish army and regain his throne, which was crushed at the Battle of Worcester. The victorious Parliamentarians tried desperately to capture him and bring him to London for trial. Attempting to throw them off the scent; instead of making straight for the south coast, and accompanied by Colonel Giffard, he fled north into Shropshire; where the Colonel owned land and estates.

Views of Boscobel House in Shropshire; the house had changed little by 1830, but by 1900 an ornate garden had been laid out

There he took refuge at Whiteladies Priory, helped by the four Penderel brothers, Richard, John, William and Humphrey, who were tenants of Colonel Giffard and lived at nearby Boscobel House. Pursued by the Parliamentary army, he famously hid in an oak tree while Cromwell’s troops searched for him below.

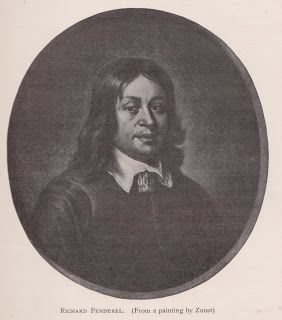

Two of the four Penderel brothers who sheltered the fugitive King. They lived at Boscobel and the King never forgot their kindness and loyalty to him

His successful escape relied entirely on his own wits, and the loyalty and kindness of the people he met, because it was so difficult for him to disguise himself convincingly. Charles was about 6’2” (taller than all but the tallest men even today), and his face was dark and saturnine (although he could at least cut off his distinctive long thick black hair).

Whiteladies Priory, where the Penderel brothers hid the King from the Parliamentarians in 1651

From Boscobel the King moved to Moseley Old Hall, near Wolverhampton, at the suggestion of Father John Huddleston, who as a priest knew the Catholic Penderels. Father Huddleston bathed and bandaged the King’s sore feet (being so tall, he found it impossible to find boots big enough to fit him). Unknowingly the Parliamentary troops followed him there, and he and Father Huddleston hid in a priest-hole while they searched the house.

After several more weeks of hair-raising adventures on the run, and for much of the time quite alone, Charles finally managed to set sail from Brighthelmstone (today’s Brighton) to France. It would be another 9 years before he saw England again. In later years he loved to tell the story of his escape, and probably became a bit of a bore about it!

Boscobel House and the Royal Oak today (photograph by English Heritage). This tree is not the original oak tree in which Charles hid in 1651, but a seedling from it that was planted to commemorate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897. In 1651 the oak was not a solitary tree, but was part of Breward Forest surrounding Whiteladies and Boscobel.

Today the Monarch’s Way, a 615-mile waymarked footpath, follows the King’s escape route, starting from the battlefield outside Worcester and ending just beyond Brighton at Shoreham, where the King actually embarked.

During his years of exile, Charles remained hopeful that a Royalist rising would restore him to his birthright; but the remaining Royalists, both in England and abroad, were heavily infiltrated with Parliamentary spies; and the last real attempt in 1655 was easily put down by Parliament. It was followed by the notorious rule of the Major Generals.

Then in 1660, with Cromwell dead and the revolutionary tide finally exhausted, Charles was peacefully, almost effortlessly, restored to his throne; at the expressed will of Parliament and the people. He rode into London on 29 May 1660, his thirtieth birthday, with his brothers James and Henry riding beside him. His spaniels rode behind in one of the accompanying carriages, no doubt with their footmen in attendance.

Charles II and his brothers in 1660

The King was so fond of his dogs that he was rarely seen without them. They accompanied him to state banquets, to council meetings and to bed, where he happily allowed them to whelp, which the fastidious diarist John Evelyn complained “rendered it very offensive and indeed the whole court nasty and stinking” (of course Evelyn was a bit of a party pooper. He used to celebrate his birthday by fasting in preparation for Holy Communion the next day).

It’s a common belief that the King decreed the spaniels’ right of free access to all the royal palaces and parks. This gave rise to the myth that they can still enter the Houses of Parliament (part of the Palace of Westminster) unhindered. Lord Rochester, one of the most acerbic of the court wits, wrote this poem about the King and his pets.

In all affairs of Church and State

He very zealous is and able

Devout at prayers and sits up late

At the Cabal or Council Table

His very dog at Council Board

Sits grave and wise as any Lord

Charles’ favourite sister Minette was also a lover of the toy spaniels, as her portrait shows. In fact, the dogs had long been as popular at the French court as they were in England: portraits of the children of Henri II and Catherine de’ Medici show them, as do those of the children of Louis XIV a century later.

Princess Henrietta Anne of England, Duchess of Orléans and Madame de France

After her death in Paris aged 26 in 1670, Charles is said to have taken all her dogs back to England with him. In fact, by then the toy spaniels had become the must-have accessory for every fashionable court lady, led by Charles’ many mistresses.

Lady Castlemaine was his first “official” mistress…

Barbara Villiers, Countess of Castlemaine

Louise de Kérouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth was sent to England in 1670 by Louis XIV to “comfort” Charles after the loss of his sister (Louise had been in Minette’s train when she came to Dover to see her brothers shortly before her death, and had caught the King’s eye). Perhaps the King, always notoriously short of money, economised by giving his ladies puppies instead of jewels!

Louise de Kerouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth

Nell Gwyn seems to have given hers to her (and the King’s) son, James Beauclerk. Poor little James was sent to Paris in 1676 for his education and died there aged 10 in 1681.

James Beauclerk, aged 5, by William Wissing

Charles’ brother James II was also devoted to his dogs. When forced to abandon ship off the Scottish coast, he immediately gave the order “Save the dogs!” followed after a pause by “…and Colonel Churchill”.

Colonel Churchill was saved and went onto become the Duke of Marlborough and victor of Blenheim; and through his wife, is indelibly associated with the spaniels whose colour commemorates his great victory – and his palace in Oxfordshire.

The Marlborough Connection and the 18th Century – Kings, Queens and More Ladies of Distinction…

Sarah Jennings, later Duchess of Marlborough, was a great favourite of King James’ daughter, later Queen Anne, and her first spaniel may well have been a gift from the Princess.

Princess, later Queen Anne and Sarah Duchess of Marlborough with their pet spaniels

While her husband was away fighting the Blenheim campaign, the Duchess in her agitation is said to have repeatedly kneaded the head of her pregnant bitch with her thumb, and as a result the puppies were all born with a red spot on their heads. This is the origin of the famous and desirable Blenheim spot.

The reign of William and Mary saw the introduction of the pug, which began to eclipse the spaniels in popularity. But by the middle of the 18th century the toy spaniels were once again the height of fashion.

Queen Charlotte had one…and so did Emma, Lady Hamilton (yes, that Lady Hamilton, but painted before she met Nelson)

In fact, the spaniels were favourites with whole royal family, and appear in portraits of George and Charlotte’s daughters too.

Princesses Mary, Sophia and Amelia, the 3 youngest daughters of George III, with their pet spaniels, in 1785

Blenheim spaniels continued to live at Blenheim Palace for another two centuries, and appear frequently in family portraits.

George, 4th Duke of Marlborough with his wife Caroline and their family – and dogs – in 1778, by Sir Joshua Reynolds

During the 18th and 19th centuries breeders had diverse ideas about what constituted an ideal King Charles Spaniel, as these paintings show.

The King Charles Spaniel by Georgian & Victorian Artists

But their appeal remained unquestioned. John Ruskin, the Victorian writer and art critic, had a Blenheim spaniel in childhood, and was a lifelong enthusiast for them.

John Ruskin in 1822, aged 3, by James Northcote

As a poet and a romantic, he couldn’t resist celebrating their charms in poetry:

I have a dog of Blenheim birth,

With fine long ears and full of mirth;

And sometimes, running o’er the plain,

He tumbles on his nose:

But quickly jumping up again,

Like lightning on he goes!

Queen Victoria, the 19th Century and the End of the Marlborough Connection

Queen Victoria continued the royal association with the dogs by having a tricolour spaniel called Dash during her teens. The dog was originally a gift to her mother the Duchess of Kent from her comptroller, Sir John Conroy, but within weeks he had become Victoria’s treasured companion.

Princess Victoria, aged 13, with her spaniel Dash, by Sir George Hayter

It says much for Dash’s charm and appeal that the Princess took him so completely to her heart, for she loathed Conroy with a passion. But Dash could do no wrong. After her coronation in 1838, aged 19, she recorded in her diary how she came home, ran upstairs and gave Dash his bath.

The Queen had Sir Edwin Landseer paint all her favourite pets…

Dash with Lory the parrot, Nero the greyhound and Hector the Scottish deerhound, 1838

…and then had Dash painted alone.

Dash, 1839

When he died in 1840, she was heartbroken. He was buried in Windsor Home Park and a marble effigy was erected over his grave, bearing this very Victorian inscription, said to have been written by the Queen herself.

Here lies

DASH

The favourite spaniel of Her Majesty Queen Victoria

By whose command this Memorial was erected

He died on 20th December 1840 in his 10th year

His attachment was without selfishness

His playfulness without malice

His fidelity without deceit

READER

If you would be beloved and die regretted

Profit by the example of

DASH

The Dukes of Marlborough continued to breed Blenheim spaniels until the beginning of the 20th century.

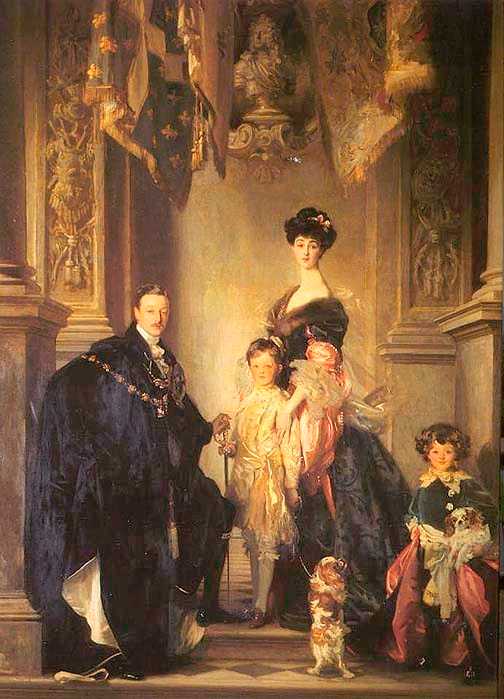

Charles (“Sunny”), 9th Duke of Marlborough and his wife Consuelo Vanderbilt with their two sons, the Marquess of Blandford and Lord Ivor Spencer-Churchill, by John Singer Sargeant

This family portrait was inspired by the 18th century one of the 4th Duke and his family; and as then the children’s Blenheim spaniels were included in the family group.

Financial necessity had led the Duke to marry a rich American heiress (a common practice at that time), but the resulting marriage was deeply unhappy. For years the Duke and Duchess led separate lives; and both struck up a friendship with another American, Gladys Deacon.

Gladys was a famous beauty, and by the early 1900s she was virtually living at Blenheim as the Duke’s mistress, with the tacit sanction of the Duchess. Her beauty was immortalised in the sculpture of the sphinx in the palace gardens; while her beautiful blue eyes are depicted in the ceiling of the north portico.

Despite her unhappy marriage, Gladys still adorns Blenheim Palace today

Eventually the Duke and Consuelo were divorced, and soon afterwards in 1921 the Duke and Gladys were married. But poor Gladys seems to have been mentally unstable (her father and grandmother also had mental problems); and soon after their marriage her relationship with the Duke deteriorated, becoming fraught and unhappy.

The Duke converted to Roman Catholicism, and Gladys’ behaviour became increasingly eccentric; she even kept a revolver in her bedroom to prevent her husband from entering. She also became obsessed with breeding Blenheim spaniels, which she allowed to defecate all over the palace, ruining the priceless carpets, to her husband’s disgust.

The Duke, “Sunny” by name to his family although evidently not by nature, moved out of the palace and eventually succeeded in evicting Gladys. (To be fair, “Sunny” was not a tribute to his beautiful nature; it was a nickname acquired in boyhood from his title at birth, the Earl of Sunderland.)

But it was also the end of the Marlborough association with the breed. The Duchess took all her dogs with her.

The Founding of the Toy Spaniel Club, and the Early 20th Century – the Birth of the Modern Cavalier

In 1886 the Toy Spaniel Club was founded to celebrate the dogs known individually as the King Charles (black and tan), the Prince Charles (tricolour), the Blenheim and the Ruby. In 1903 the Kennel Club proposed ending the confusion by dropping all reference to the royal connection and classifying them all as the Toy Spaniel. But (rather illogically, as they had invented it) the Toy Spaniel Club was horrified. However, they seem to have been well-connected, and when King Edward VII indicated that he preferred the royal name, the King Charles Spaniel was formally recognised by the Kennel Club as a new British breed.

King Charles Toy Spaniels from Cassell’s Book of the Dog, 1881

By this time many of the spaniels had become increasingly short-nosed and domed in the head, probably through interbreeding with pugs to produce what was the fashionable look of the times. And when an American gentleman called Mr Roswell Eldridge came to Britain hoping to see the spaniels like those in the old royal portraits, he was so disappointed by what he found that in 1926 he offered a prize at Crufts; £25 each for the best dog and best bitch of the old-type spaniels. He was looking for flatter heads and longer noses, or to quote Crufts’ catalogue: “As shown in the pictures of King Charles II’s time, long face, no stop; flat skull, not inclined to be domed and with the spot in the centre of the skull”.

Mr Roswell Eldridge, father of the modern Cavalier

Only 2 entries came forward in that first year, but the award was later extended from 3 to 5 years, which stimulated competition while it lasted. In 1928 a breed club for the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel was founded, although the Kennel Club refused to accept it as a separate breed and listed it as the King Charles Spaniel, Cavalier Type. The breed standard was also drawn up at this time, and remains largely unchanged up to the present day.

Two of the founders of the breed were Miss Mostyn Walker, owner of a Blenheim dog called Ann’s Son (who was the model for the breed standard); and Mrs Amice Hewitt Pitt, who adopted the prefix “Ttiweh” (“Hewitt” backwards), with a Blenheim bitch called Waif Julia.

Ann’s Son was bred by Miss Mostyn Walker sometime around 1924 out of a bitch unsurprisingly called Ann, by a Blenheim dog called Lord Pindi. There were two dogs in the litter, both of very classical Cavalier type, and both became prolific stud dogs.

Ann’s Son, one of the founders of the modern Cavalier

Mrs Pitt, who was a well-known breeder of Chow Chows, bought Waif Julia in 1924 as a pet for her mother. When, on being urged, she entered the bitch in Mr Eldridge’s sponsored class and won it, she became interested in breeding this original type of King Charles spaniel.

At first there were just 6 breeding dogs, from which all present day Cavaliers descend: Ann’s Son, his litter brother Wizbang Timothy, Carlo of Ttiweh, Aristide of Ttiweh, Duce of Braemore and Kobba of Kuranda. Inevitably there was a fair bit of in-breeding at the start, to which a lot of the health problems of modern Cavaliers can probably be traced. In those days it was known as line-breeding, and was considered acceptable and even a good thing, as it was meant to preserve the desirable qualities in a breed line.

Progress was slow at first, as no Challenge Certificates were offered and few people had much interest in a breed with little or no sales value. But gradually the little spaniels became more familiar to the public, and their charm and appeal led their popularity to rise.

One of the little known tragedies of World War II was the destruction inflicted on Britain’s dog population. Much of the breeding stock was destroyed because people did not have the resources to feed them or the time to nurture them. By the end of the war, the Ttiweh kennel had dropped from 60 dogs to just three.

The Later 20th Century and the Rebirth of the Cavalier as a Universal Favourite

In 1945 the Kennel Club finally recognised the Cavalier as a separate breed. Gradually the numbers increased and the Cavalier overtook the King Charles Spaniel in popularity, to the point where the King Charles is now an endangered breed.

In 1946 the first set of Challenge Certificates was issued. The first champion was Daywell Roger, a grandson of Ann’s Son, owned (though not bred) by Mrs Pitt’s daughter, Jane. He was very widely used at stud.

Ch. Daywell Roger, first Cavalier champion dog in 1946

By 1960 the number of Cavaliers registered by the Kennel Club had reached 4 figures, and in 1963 a Blenheim bitch, Amelia of Laguna, won the Toy Group at Crufts.

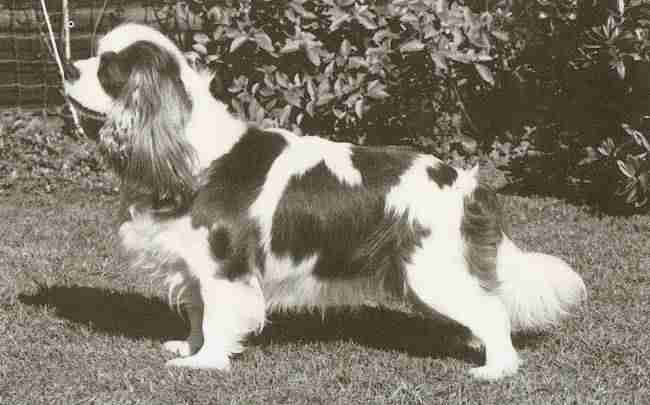

Ch. Amelia of Laguna (photograph by Sally Anne Thompson)

By the early eighties registrations had reached 10,000 and separate judges were needed at shows for each sex. The little spaniels continue to top the Toy Group at Championship shows, and regularly win the Best in Show title.

3 great Cavalier champions; Lymrey Top of the Pops and her sons Lymrey Royal Reflection of Ricksbury and Lymrey Royal Scandal at Ricksbury

Mr Eldridge didn’t live to see the success of his quest, but he would be pleased to know that today Cavaliers are equally popular in America, with one of them even becoming the First Dog during the presidency of Ronald Reagan. Appropriately enough for a royal dog, he was called Rex.

Ronald and Nancy Reagan with Rex, the First Dog

The breed is now well established throughout the world with an increasingly diverse breeding stock, and effective tests to help eradicate many of its hereditary weaknesses.

I’m sure King Charles II would have been tickled pink!

Charles II as a young man of 23 in exile…and as he looked in 1665, five years after his Restoration, when he was aged 35

It’s clear that the intervening years had not been kind to him.

In the 17th century a man of 30 was not a young man as he would be today, but a man on the verge of middle age with half his life behind him. In fact Charles died early in 1685, aged 54, probably killed by his over-enthusiastic and staggeringly incompetent doctors. Just before his death, he was received into the Catholic church by Father Huddleston, the priest who had sheltered him during his escape from Worcester 34 years before.

I’ve always thought he bears an astonishing resemblance to the dogs named after him – the black and tan ones, at least!